I recently read Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, by Neil Postman. It was a Father’s Day gift from one of my daughters. First published in 1985, the copy I read was updated by Penguin Books in 2005 for a 20th Anniversary Edition featuring a new introduction by the author’s son, Andrew Postman. The book argues that electronic media — and television in particular — are degrading our national discourse.

One of Postman’s central points is that the United States was formed in an era dominated by print media and a culture of literacy. His contention seems to be that the entire political system rests on the capacities that print media require of us as readers. Postman gives a brief listing of these capacities:

“…in judging the quality of an argument, you must be able to do several things at once, including delaying a verdict until the entire argument is finished, holding in mind questions until you have determined where, when or if the text answers them, and bringing to bear on the text all of your relevant experience as a counterargument to what is being proposed.” (p. 26)

All of these capacities require a strong short-term or working memory, access to long-term memory, and the ability to maintain the focus of our attention over time in such a way that this information can be compared, ordered, and made sense of. Taken together, all of these things are needed to engage in critical thinking.

Postman published this book prior to the widespread use of computers in everyday life. But he saw what was coming. It amused me to read his discussion about what he calls “microcomputers” and realize that he was referring to devices like the ones through which we are now communicating. Microcomputers. That’s what they called them then.

However, even without widespread access to internet-connected devices, Postman argues that good old-fashioned broadcast TV had proven quite adequate to profoundly change public discourse and how we conceptualize our world. Postman notes, for example, that the average camera shot on network television back then was 3.5 seconds. (p. 86) His point was that this and other features of television as a medium lead to fragmentation and decontextualization of media content. In fact, Postman titles one chapter “Now…this,” a standard phrase used by newscasters to link a series of otherwise unconnected reports. On page 100 he points out, “Viewers are rarely required to carry over any thought or feeling from one parcel of time to another.”

The results of such fragmentation and loss of interpretive context are profound. Here’s what Postman says:

“My point is that we are by now so thoroughly accustomed to the ‘Now…this’ world of news, a world a fragments, where events stand alone — stripped of any connection to the past, or to the future, or to other events — that all assumptions of coherence have vanished. And so, perforce, has contradiction. In the context of no context, so to speak, it simply disappears.” (p. 110, italics in original)

This observation itself comes in the context of a discussion about a 1983 New York Times article attributing a decline in the news coverage of President Reagan’s “misstatements” to lack of interest in the general public. In other words, if we are to take the report at face value, the president was saying things that didn’t make sense, and people didn’t care. And, just as a reminder, this was already happening in the 1980s.

If we can’t compare what was said last week with what is said this week, or compare what we are currently hearing or reading with other documentable realities — in other words, if we cannot construct a “context” — as Postman points out, there is no possibility of contradiction. And without the possibility of contradiction, reason itself basically goes out the window. In such a scenario one might legitimately wonder why the words of the president are worth reporting on at all.

Unless, I suppose, what we call (in serious, authoritative tones) “The News” has been reduced to mere entertainment. And, as Postman notes, this is exactly what is implied by the production values of modern newscasting, in everything from the news programs’ opening theme music and attractive talking heads to the atomized dissociation of all news content. (pp.102-103) All of this communicates, basically: You are watching a TV show. Got that? It’s a show. Hence, also, Postman’s subtitle: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business.

And we got used to it. Consider this observation from Postman, which I believe relates:

“There is no more disturbing consequence of the electronic and graphic revolution than this: that the world given to us through television seems natural, not bizarre. For the loss of the sense of the strange is a sign of adjustment, and the extent to which we have adjusted is a measure of the extent to which we have been changed.” (pp. 79-80)

Remember when the starkly Orwellian term “new normal” started gaining circulation? When I first heard the term “new normal,” it shocked me. Now it seems perfectly normal to say “new normal.” It doesn’t seem strange anymore. Which illustrates Postman’s point.

Ironically perhaps, given the subtitle, the book itself is very entertaining to read. Many parts are delightfully reminiscent of a witty “betcha’ didn’t know” Bill Bryson book, and in its insightfulness and readability it feels a bit like Michael Pollan. Strangely, speaking as a person whose brain has been shaped by TV, finding this hard-copy, printed book entertaining to read presents exactly the same issue as does the entertainment factor in newer media: It’s easy, while reading a text that prompts occasional giggles, to lose sight of the seriousness of what Postman is saying. Consider this passage:

“[Aldous] Huxley grasped, as [George] Orwell did not, that it is not necessary to conceal anything from a public insensible to contradiction and narcotized by technological diversions. Although Huxley did not specify that television would be our mainline to the drug, he would have no difficulty accepting Robert MacNeil’s observation that “Television is the soma of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.” Big Brother turns out to be Howdy Doody.” (p. 111)

Now, that’s a catchy punchline for a readership that gets the cultural reference to Howdy Doody, a puppet character from an iconic 1950s children’s TV show. Personally, I think Orwell rides quite a bit higher in the mix today than at the time Postman wrote this book, but it’s important to remember that there’s nothing benign about being “narcotized,” since basically that means we are rendered insensible. A lot of what Postman does in his writing here is to help make things we’ve become numb to sensible to our perception.

Part of the challenge is that we live, as much as ever, within a cultural mythology. Citing the work of French philosopher Roland Barthes, Postman describes myth as “…a way of understanding the world that is not problematic, that we are not fully conscious of, that seems, in a word, natural.”

We’ve acclimated to a popular culture that has been largely reduced to entertainment. But interestingly, it’s not the fluff-and-garbage TV programming that Postman most objects to. In his view, that’s what the medium is best suited for: triviality. Indeed, citing some popular shows of that era toward the end of the book, Postman says: “We would all be better off if television got worse, not better. The A-Team and Cheers are no threat to our public health. 60 Minutes, Eye-Witness News, and Sesame Street are.” (p. 160)

I could quibble about the idea that television of any kind is “no threat to our public health,” but I do see how in all programming, including so-called educational programming for children, the deeper lesson is: “Stare at the screen.”

And to be clear, Postman doesn’t exactly say that TV turns people’s brains to mush. In his words: “My argument is limited to saying that a major new medium changes the structure of discourse; it does so by encouraging certain uses of the intellect, by favoring certain definitions of intelligence and wisdom, and by demanding a certain kind of content…” (p. 27)

So he doesn’t exactly say television turns brains to mush. But it’s hard, reading this book, to conclude otherwise.

And my observation is that, given the way we engage with the internet through our computers and handheld devices — or as I like to call these things, “The Television That Watches Us” — it’s doing much the same thing. Channel surfing, meet internet scrolling. Scroll, meet surf. I’m sure you’ll get along just fine. Ms. Binge Watching, meet Mr. Incessantly Check Your Phone. I think you’ll make a great couple.

What matters is what to do about all this. Reading Amusing Ourselves to Death might be a good start. So might a voluntary electronic media blackout. And just for the record, I do take exception to some of what I see implied toward the end of the book and earlier (see for example pp. 139-140), where it might seem to the reader as if all this just sort of “happened” due to some unforeseeable consequences of technological development. I don’t think this is necessarily the case. Consider this quote from Postman, who writes:

“What is happening here is that television is altering the meaning of ‘being informed’ by creating a species of information that might properly be called disinformation. I am using this word almost in the precise sense in which it is used by spies in the CIA or KGB. Disinformation does not mean false information. It means misleading information — misplaced, irrelevant, fragmented or superficial information — that creates the illusion of knowing something but which in fact leads one away from knowing.” (p. 107, italics in original)

Personally, I find it hard to believe that our local disinformation professionals would overlook such rich possibilities for public deception, which Postman argues are inherent in the deep structure of television as a medium. Likewise, if we notice ourselves becoming dependent on a product of intentional engineering like TV or cell phones, I think it’s probably worth considering that our state of dependency was itself intentionally engineered. And if so, to whose benefit? I mean, what off-camera entity is really pulling Howdy Doody’s strings?

Anyhow, there’s a lot to think about here. Postman often says a lot in a single paragraph or page, and all of it has relevance today.

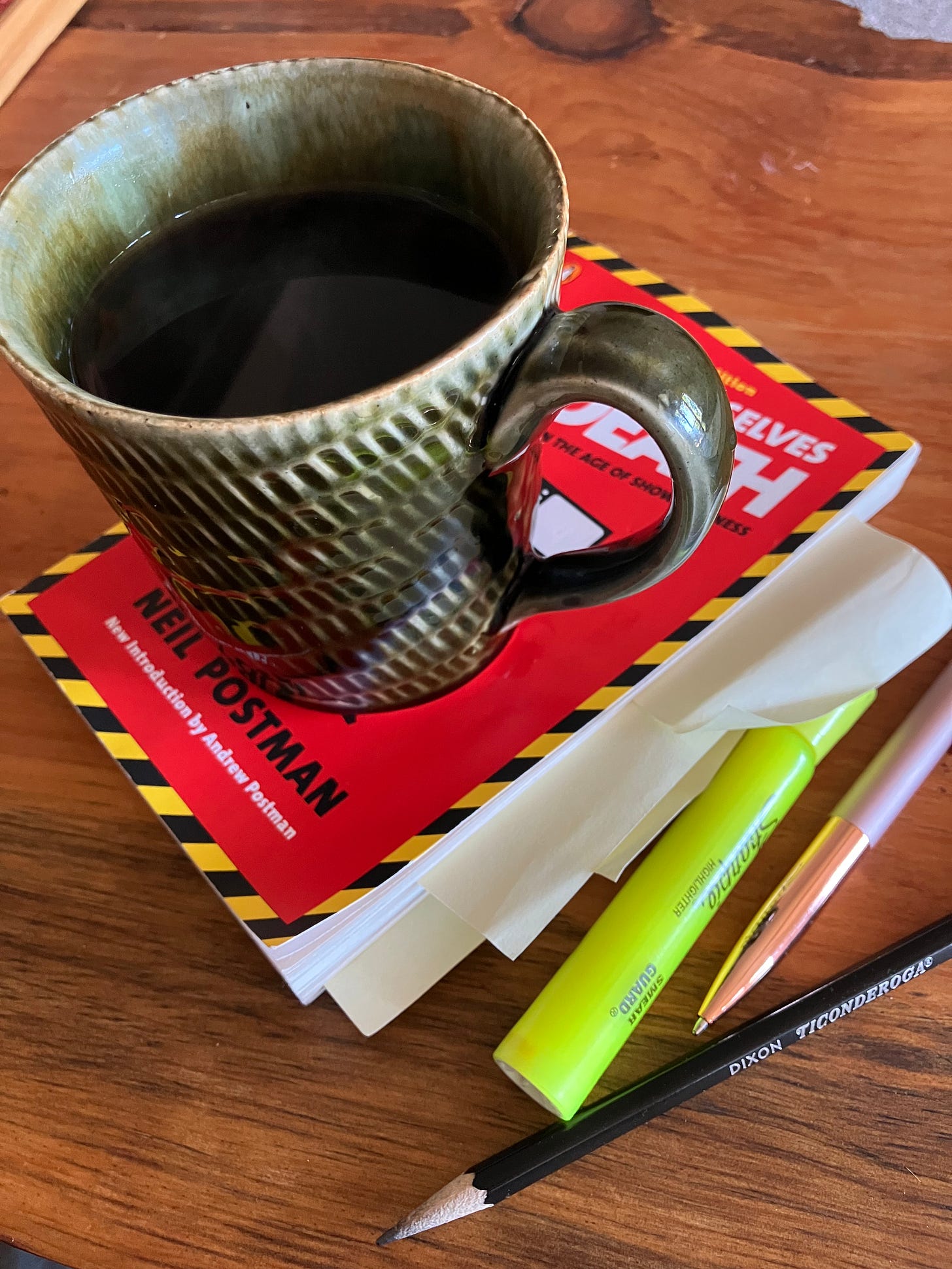

Of course, to access the deeper implications of what he says we should not be reading this book as though we are scrolling an internet feed or watching a TV news show. My own softcover copy is only about a month old and already it is dog-eared, stuffed with sticky-notes, scrawled in the margins, and yellow with highlighting. In time there will probably be a coffee ring on the cover. I’m surprised there isn’t one already. It’s a classic sign of a book you just keep coming back to.

All of these are indicators of “old school” engagement with a piece of writing. For example, when I reached page 51 and found something that seemed to subtly contradict assertions made on page 27 — seemed to, I must emphasize — I went back and checked. That means I remembered on page 51 something I’d read on page 27. This kind of engagement is the very opposite of the wispy kind of cotton candy brains encouraged by electronic media like television, and if Neil Postman were still alive I’m pretty sure he’d approve.

This was such an interesting read, Cliff. Older generations do tend to bemoan any new technology while younger generations say we are being stuffy and afraid of change. But there is argument to made about what we do with the technology we create and the long-term impact it has on our lives, whether that is at the expense of convenience or entertainment. Thanks for posting this.