Carolyn stood alone by the window in her father’s ancient study, the floor creaking beneath her in tones of mild disapproval as she shifted her weight at intervals from foot to foot. Well, she never could stand still. Especially while waiting. And this was not a meeting she looked forward to. The only bright spot today would be seeing Aunt Rose.

As she glanced toward the door, the room looked much as it always had when she was growing up, neither spacious nor cramped, although the dark polished furniture and paneling now bore a trace of dust. Located at the rear corner of the first floor of the house, the heat never seemed to reach this room. Even now, the air had a bit of chill, although she could see through the window the estate’s orderly annual uprising of daffodils and tulips in the afternoon sun, announcing the arrival of spring.

Carolyn unlatched and tried to lift the double-hung window, hoping for a breath of the air beyond. It was stuck. She recalled in a flash how, as a high school senior, with her first boyfriend Anton outside and her tugging these same brass handles inside, by working in tandem they had managed with difficulty to raise this very window late one night as her parents performed unwitting sentry duty in the sitting room near the front of the house. Bonnie the maid blocked the kitchen entrance working late to finish party preparations for the following day. Mindful of the squeak-prone floors, they had, as planned beforehand, disguised their twosomeness by walking with synchronized steps, Marx-brothers-style, all the way upstairs, suppressing terrified giggles until they reached her bedroom and secured the door.

They were never discovered. Nor did they attempt it again. But that was years ago, a time of testing boundaries, a time when her mother, a woman of breeding as she imagined, had advised Carolyn to “Stop wearing blue jeans in public if you ever want to go anywhere in life.” Now dressed in business attire and heels, Carolyn gave the brass handles of the window another helpless tug. Nothing.

Anyhow, the books were the same, rows and rows of them. When Carolyn was a member of this household she’d pored through quite a number of these titles over the years. The privilege came with the explicit understanding that only one book at a time could be withdrawn and that each must find its assigned place among the others when she was through with it. There were some great, even earth-shattering ideas sitting on these shelves, or so she recalled thinking during her teen years. Also held tightly in their pages, the dankly aromatic remnants of her father’s pipe smoking days still found their way to Carolyn at odd moments, startling her with surprising closeness.

However, despite the sequenced and cumulative detonation of insight within her when she had first acquainted herself with these works, the earth had not shattered. And honestly, during the intervening years it seemed more like the world had simply been eroded and chipped away, taking on a shape progressively less prone to further fracturing, like the head of a stone mallet. No, the world was no longer breaking as it had when she was a teen— breaking open, that is. Again she thought of Anton, and for a moment pressed her lips a little more tightly together to suppress both the flicker of a smile that his memory elicited and the frown that quickly followed it. To distract herself, she wondered as she scanned the shelves which of these she last read, and if perhaps in a younger person’s hands the poetry sitting here in quiet repose still held such power within it. She guessed it might, were these books taken elsewhere. The study, though orderly, had fallen into disuse. When her mother was still alive her parents had opted to settle in the front room with no stairs to challenge them and a bathroom nearby. There, the endless profanity of cable television had transfixed them in their side-by-side recliners for more than a decade before they passed, her mother leading the way.

So if secrets still waited to be discovered on these shelves, they would yield their gifts only elsewhere, and only to fresh and lively intelligences determined to ferret them out. Such, she now mused, was hers, once, though she was by no means certain that their value would be extractible by more recent generations. One way or another, it would all be going, soon enough.

But more than anything, this is what the contours and colorations of her father’s literary tastes had revealed to Carolyn growing up: His portrait in books, and poetry most of all, of course. Could it be helped that it was the portrait of the very much younger man who had collected them? What other picture could emerge when combining, say, W.B. Yeats and D.H. Lawrence? Thus by opening books and turning pages — the books themselves randomly selected, pulled by dint of title, impulse or mere proximity — Carolyn got to know her father. She found a man as yet unmarried, weighed down by books as bibliophiles tend to be, but unencumbered by the mundane obligations and attendant pettiness that invariably exact a toll on young men who start out pursuing great ideas and then ultimately yield to the blunt instrument of passing years.

At length Carolyn sat down in that tentative way one does on old needlepoint. She’d wanted to be standing when they arrived, but the reverberations of this cavernous old building would likely give warning enough. During childhood she had often knelt on this burgundy settee with its muted floral motifs, set beside the mahogany table with its globe. Now she extended her arm and rested a hand upon the globe, feeling its gentle curve filling her palm as she easily spanned from the Americas to Europe from thumb to pinkie. Yes, it was a classic globe in a table stand, as if this were a movie set for a scene where business magnates in top hats planned voyages to plunder the riches of Asia or Africa. But this globe had a wide pinkish swath of Soviet Union wrapping itself halfway around the pole—the era of plunder and empire-building via wooden ships had by the time of its manufacture been succeeded by a period with different means of accomplishing similar ends. That’s not what she’d thought about as child, however. As a girl the main thing was to wonder at roundness of the world, the islands and continents adrift on the seas looking like fantastic creatures caught in the midst of dramatic transformations. As long as little Carolyn stayed quiet, she could study this globe, her father sitting at his enormous desk, a mere three girlish strides away. By age eight, she practically knew it all by heart.

…if you ever want to go anywhere in life...

Yes, Mother. Thank you for your opinion.

Carolyn removed her hand. The settee under her full-grown weight seemed even more reluctant to support her than it used to, and after a minute she stood again. The seat was an antique anyhow, placed there specifically since odds were nobody much would sit on it. Besides the settee, there had never really been a place for Carolyn in her father’s study, nor for anyone else, come to think of it, save the impersonal visits of those whose job it was to keep it clean. It seemed so by design. And mother never visited this room, toeing a boundary just inside the threshold even during the years when father regularly stoked the fireplace to push the chill back on many a winter Saturday afternoon. Still, as a girl Carolyn had walked straight through, unrestrained by any such invisible fence. In fact, when she could, she had flaunted her ability to do so, if only to take her uncomfortable place by the globe.

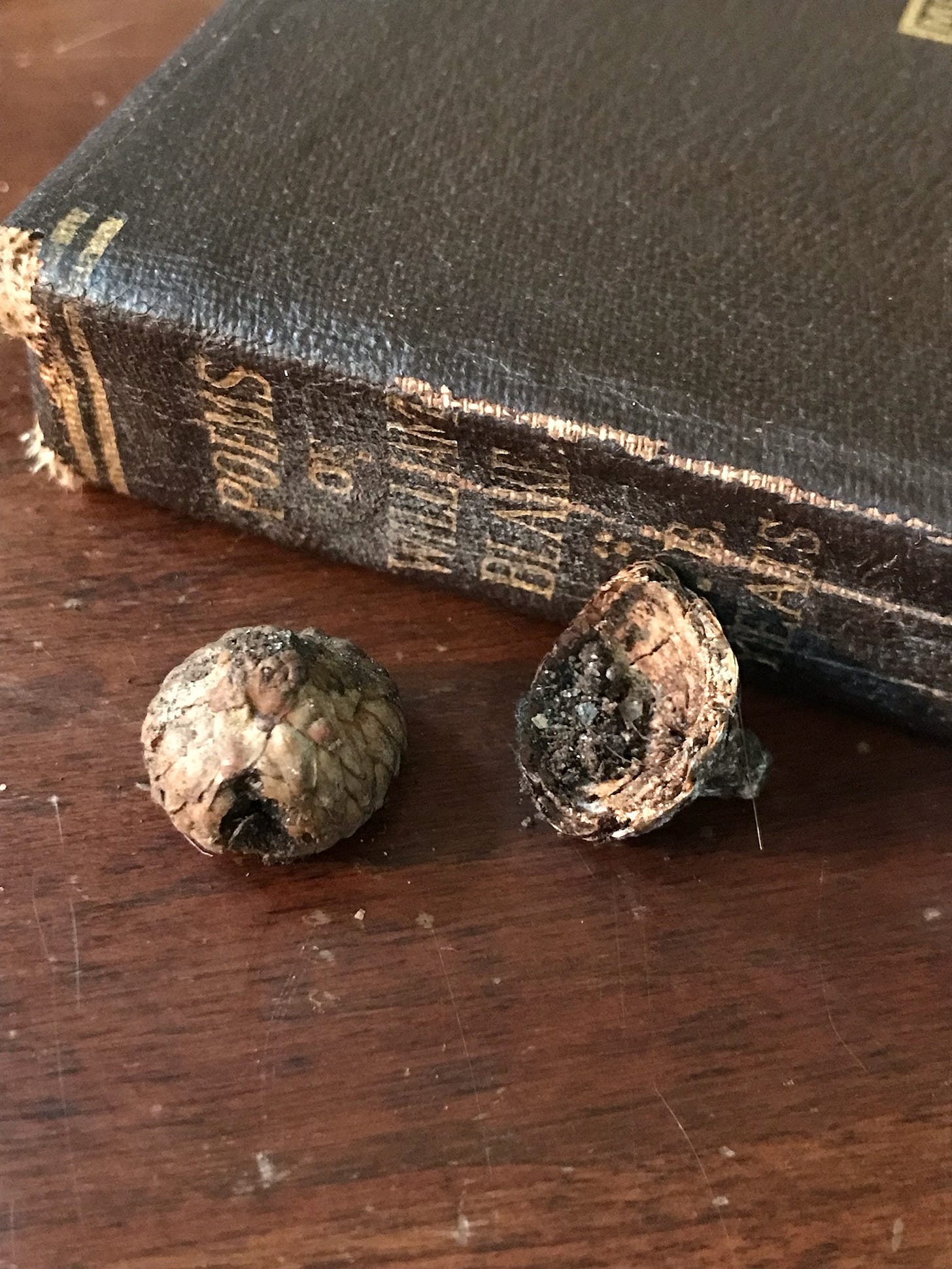

That said, something inside her bowed deeply before it all, now as then, when she’d played Nancy Drew taking in the scene of the crime when her father was away on business. She never dared so much as to pull open a desk drawer, however. Carolyn now stepped over to look at a few mementos on a bookshelf: an acorn, college track team photo, a framed award from work, a length of faded lavender ribbon. She pondered especially about the acorn, which had been picked up and dusted under by such a long sequence of housekeepers that even the cap had taken on a polished look. Playing with that acorn in her pre-teen years, Carolyn had pulled the cap off once. Horrified, she glued it back on with Elmer’s and never told a soul.

She’d always wondered: why these particular things? What were their stories? About the acorn, as an early teen Carolyn had wanted to imagine that perhaps her father had picked it up while walking on a date with her mother, putting it in his pocket absentmindedly, maybe to free his hand for hers. Now Carolyn picked it up and looked at it, the cap still securely glued in place. Anyhow, it was a sweet thought, and not too far-fetched given that her father had apparently read Tennyson and Wordsworth at one time. Funny she never thought to ask about it. Later in her teens, and wiser, as she thought, in the ways of men, she decided that if there were any romantic significance in the history of this acorn, her mother likely did not play a part in it. Precisely not Mother, Carolyn had reasoned. Anyone but. This gave rise to more intriguing and exciting speculations, since people tend to hold longest to the things that remind them of what they have lost. The one that got away. Years later, when she caught sight of it while home on a family visit, she had to smile: It could be about mother after all, and it could be about love, the magic of courtship being the fleeting thing it so often had proved to be. Something almost always gets away from us, after all.

Now in her 50s, she realized with a combination of amusement and perplexity that the acorn could mean anything or nothing at all, or its meaning could be forgotten, like that quote she remembered from Robert Frost: “Only God and I knew what I meant when I wrote that; now only God knows.” Stranger still, its significance could be in a state of continual self-transcendence, a thought that would certainly have pleased her hippish literature professor freshman year at Columbia. But in fact, this seemed most demonstrably true. How many ways to tell its story? Here’s one, she thought, though of course by no means definitive: An ordinary acorn elevated by chance only to die on a bookshelf with the greening, wooded backdrop of the property visible through a nearby window.

So much for poetry. Dammit.

She walked to the window, thought about giving it another try and heaved a sigh. Everything needs to be opened! Everything!

Then Carolyn heard a sound from the front of the house. It was time. She turned and a few moments later a woman appeared at the study door. It was Aunt Rose, her father’s sister. But Rose had stopped short; apparently Father’s invisible fence still worked, even now.

“Hi Carolyn, dear. I got here at the same time as the men from the rental place. I let them in. They are taking out the hospital bed and equipment. The appraisers said they are running a little behind. They’ll be here in about a half hour. I’ll be happy to stay while you talk with them…” Their eyes locked for a moment. “Come here, dear.”

Carolyn obeyed. They hugged for a moment in the doorway and then heard more sounds coming from the front hall. Rose reached for Carolyn’s hand. The acorn was still in it. Carolyn slipped it into her pocket and put her hand in Rose’s. Aunt Rose gave a little squeeze in reply and they walked together down the wide main hallway.

The rental people had propped the front door open and were in process of taking out the clunky metal bed, to be followed by other things of bitter medical necessity. When the path had cleared, Rose led Carolyn down the front steps and into the cool sunshine, a sudden breeze briefly lifting the hair off their shoulders before it rushed into the open door of the house behind them.

Subtly moving.