Last week while Mary was out of town I read a translation of a four-chapter novel called Before the Coffee Gets Cold by Japanese author Toshikazu Kawaguchi. The premise of this book is that if one sits in a certain chair in a particular cafe, one can travel in time — for the duration of the warmth of a cup of coffee. You must return before your coffee goes cold.

After reading the very first chapter I felt compelled to read on. I thought the author said something very important with his storytelling, even if there is a somewhat facile sidestepping of the time-travel paradox. Subsequent chapters kept me reading, and overall I’d recommend the book, which according to the cover has already sold over a million copies. But in the last chapter I encountered something that really shocked me: it came across a literary ploy in which a character elucidates, in sequence, the key takeaways from the previous chapters.

I can only imagine why the author decided this was necessary. Weren’t we there with him through the story? Didn’t Kawaguchi trust we’d understand and derive our own conclusions from the tales he wove together and the characters’ experiences within them? It’s not a very long book. Can’t we figure stuff out? Can the readership be trusted to recall what happened in the first chapter by the time we reach the last one?

Much as I enjoyed reading Before the Coffee Gets Cold, when I got to that part, as a reader, I felt vaguely insulted. As a writing coach, I found myself asking if such a literary device were really necessary. It brought up a question I often find myself pondering in my work, which is how much handholding and how much spoon-feeding authors owe their readers. When does it help, and when does it get in the way?

My guess is that by spelling out the meanings of the stories and by reminding readers of what happened in first chapter when they reach the final chapter, the author had probably grown his readership. Doing so likely made the ending of the book more comprehensible and satisfying to many, and thus easier to recommend. At the same time, I recall how I felt while reading chapter one when the author’s message came through without that kind of heavy-handed “help,” and how this sense of personal discovery and intrigue pulled me forward into the novel.

Anyhow, rather than whine about it I guess I should probably l happy that there are, for the moment, still readers of books. Can a generation conditioned by the mindless and momentary titillation of scrolling still decode the deeper dimensions of a literary work? Can a society conditioned by multiple generations of flashing pictures on screens and the schizoid influence that this has on the mind pull it together to form a coherent picture of the world? Reading books can help. Books seem to be inherently less passive and less stupefying than other media.

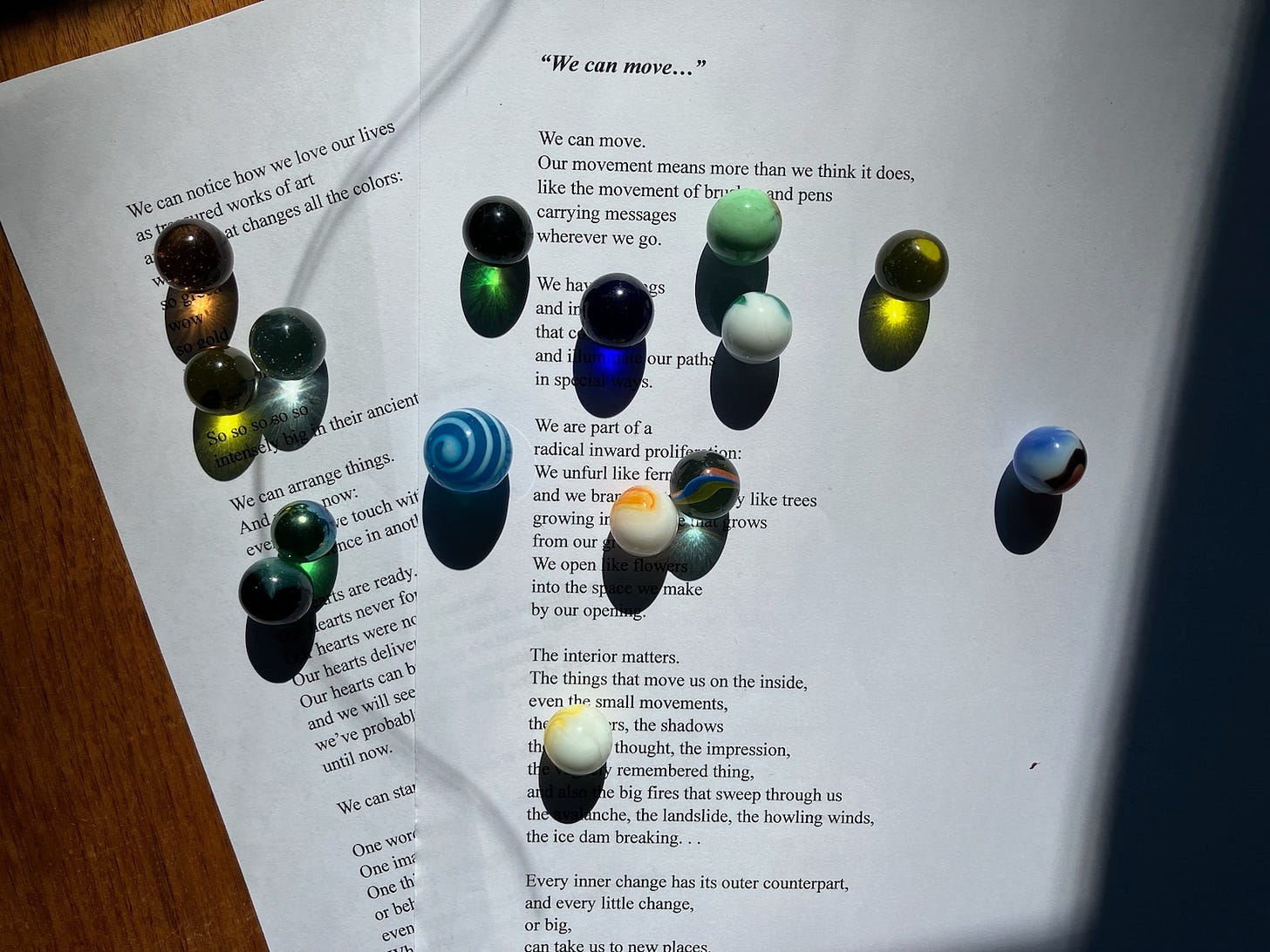

The image that comes to me is of a clear glass marble rolling across the printed page. As a lens, the marble only brings one word at a time into focus. As soon as it rolls on, the word disappears, its image and meaning and reverberations no longer reflecting and refracting within that sphere. Thing is, that’s okay. In a way that’s what reading is, because in a way that’s what life is: one word at a time passing under our lenses or one moment at a time passing through our experience. And it works, as long as we have the capacity to remember the word or the moment that just passed and make the kinds of multileveled connections among words and moments that allow them to convey their larger meanings.

If we don’t have the capacity to recall and make those connections, whatever we’re reading or experiencing won’t make much sense. Or maybe it will only make a superficial kind of sense.

So, going back to the choice Kawaguchi made in having a character summarize his book in the final chapter: if, as I suspect, the capacity of recall is a little bit diminished for many of us, the literary choice of assisting readers in remembering the story may simply be a realistic artistic option. It reflects where people are. But think of toddlers, who are spoon fed from infancy by their caregivers; they don’t want to be spoon fed forever. Toddlers want to grab the spoon and learn how to feed themselves. The same is true of readers who want to get more from their reading. As with toddlers learning to feed themselves, this can be a little messy and take more time as we discover the inherent meanings and make our own connections with the material, but in the end it’s more satisfying, so it’s worth it.

Come to think of it, seems all of this might have some political implications as well. How many political careers would end if large numbers of citizens clearly remembered what these same folks said and did in “previous chapters” — be it last year, ten years ago, heck, maybe even just yesterday or last week? By better remembering the past we might be able to draw some reasonable conclusions about these people’s intentions, motivations and capacity for honorable comportment in public life. My current read on the election cycle here in the U.S. is that if we were to add even a smidgen of recollection and critical thinking, it starts to look a lot like an enormously diverting ritual of collective humiliation. It simply does not reflect well.

With history as we live it as with the stories we read in books, we can sometimes tease out meanings in the current chapter we’re on if we remember facts, details, connections and significances from the chapters that preceded it. Personally, I read for a living. From what I’ve seen, there’s no final or definitive read on anything, just successive, nuanced approximations, punctuated at times by moments of dramatic revelation as new meanings and connections are made.

This means we have to keep at it. It’s work. It takes effort. And, it’s understandable that many people either can’t or don’t want to expend the effort needed to be part of any change they want to see in the world. But that’s what’s required of us if we are to get a better read on how we got here, and then take our story in a different direction.

[Note: full text of the poem featured in photo can be found here]

Yes. Underestimating readers is counter-productive. They may get turned off and stop reading. I have read poems and even essays here on substack that are "explained" to the readers. It's weird and annoying.